The Rise of Batteries in Six Charts and Not Too Many Numbers

The unstoppable rise of batteries is leading to a domino effect that puts half of global fossil fuel demand at risk

Battery demand is growing exponentially, driven by a domino effect of adoption that cascades from country to country and from sector to sector. This battery domino effect is set to enable the rapid phaseout of half of global fossil fuel demand and be instrumental in abating transport and power emissions. This is the conclusion of RMI’s recently published report X-Change: Batteries. In this article, we highlight six of the key messages from the report.

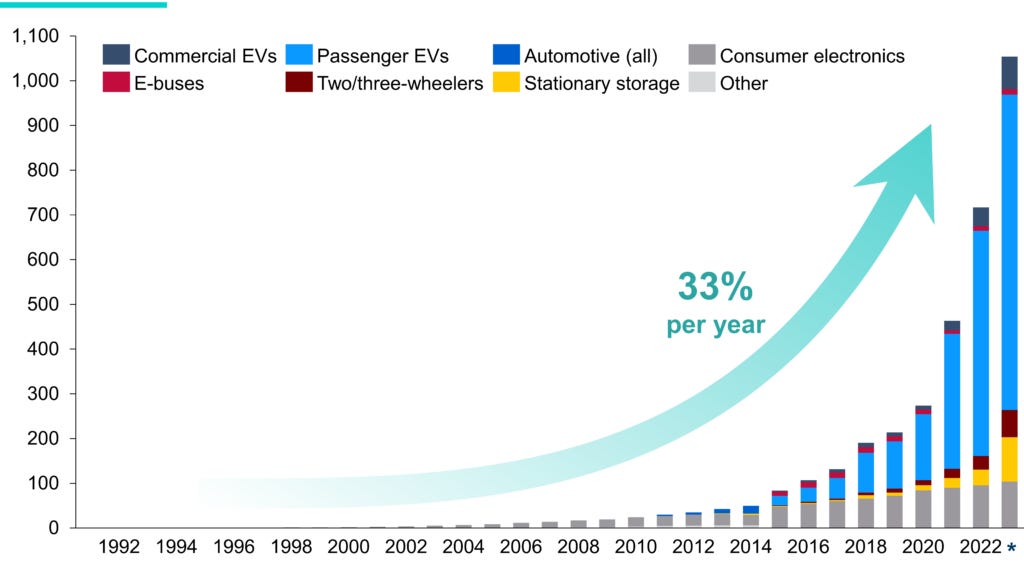

1. Battery sales are growing exponentially up S-curves

Battery sales are growing exponentially up classic S-curves that characterize the growth of disruptive new technologies. For thirty years, sales have been doubling every two to three years, enjoying a 33 percent average growth rate. In the past decade, as electric cars have taken off, it has been closer to 40 percent.

Exhibit 1: Global battery sales by sector, GWh/y

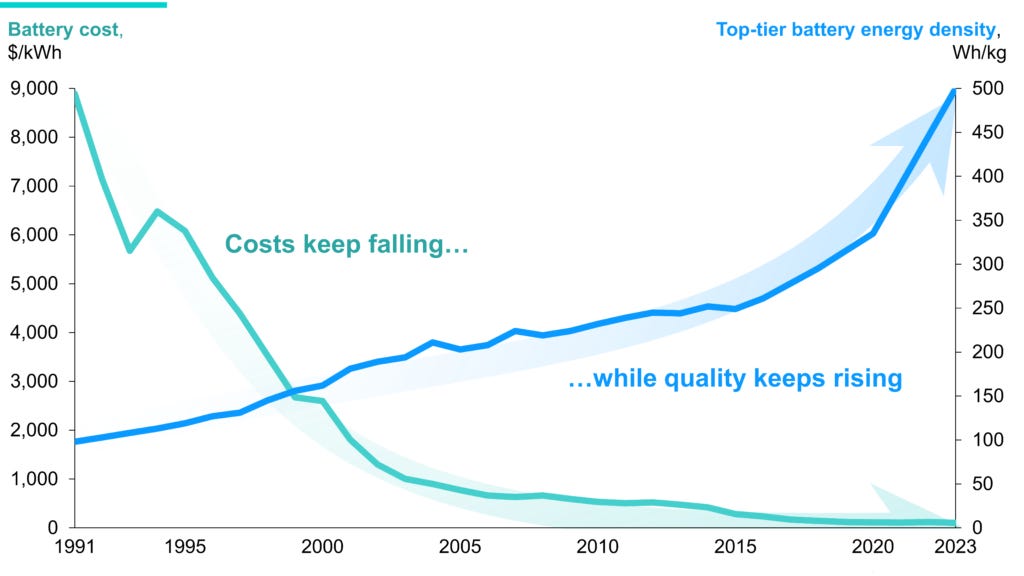

2. Battery costs keep falling while quality rises

As volumes increased, battery costs plummeted and energy density — a key metric of a battery’s quality — rose steadily. Over the past 30 years, battery costs have fallen by a dramatic 99 percent; meanwhile, the density of top-tier cells has risen fivefold. As is the case for many modular technologies, the more batteries we deploy, the cheaper they get, which in turn fuels more deployment. For every doubling of deployment, battery costs have fallen by 19 percent. Couple these cost declines with density gains of 7 percent for every deployment doubling and batteries are the fastest-improving clean energy technology.

Exhibit 2: Battery cost and energy density since 1990

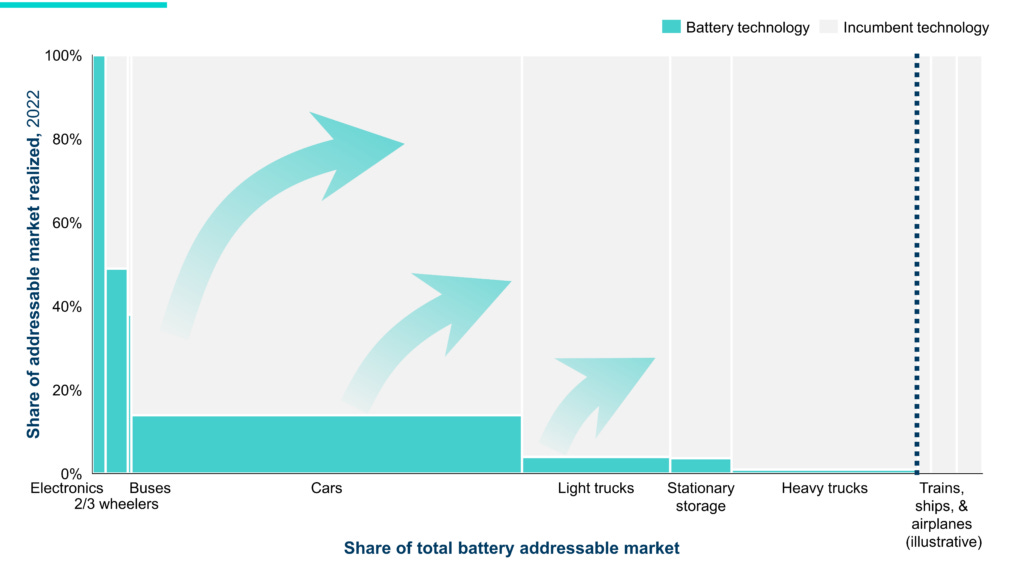

3. Creating a battery domino effect

As battery costs fall and energy density improves, one application after another opens up. We call this the battery domino effect: the act of one market going battery-electric brings the scale and technological improvements to tip the next. Battery technology first tipped in consumer electronics, then two- and three-wheelers and cars. Now trucks and battery storage are set to follow. By 2030, batteries will likely be taking market share in shipping and aviation too.

Exhibit 3: The battery domino effect by sector

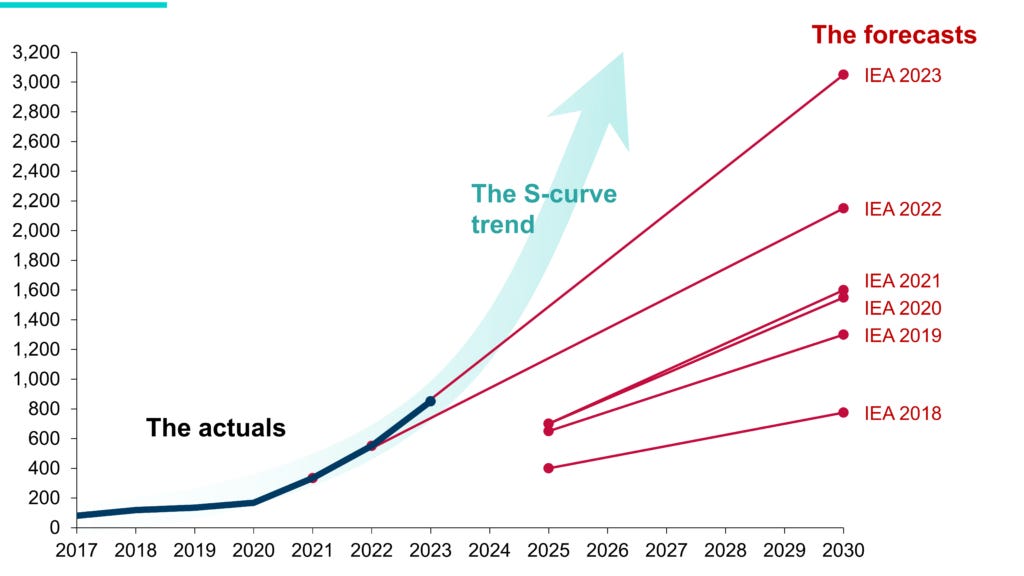

4. Incumbent modelers remain behind the curve

How fast will batteries continue to grow and improve? The answer is a lot faster than today’s consensus view. When it comes to the growth of small modular technologies, there are two rules of thumb: the first is that superior technologies undergoing rapid cost decline tend to grow exponentially; the second is that most analysts miss the first. Batteries have been no exception to this rule, having been consistently underestimated by modelers.

Over the past years, many battery forecasts have effectively projected linear growth. As Exhibit 4 illustrates, actual sales keep outrunning such forecasts and as a result analysts keep revising their projections upward. The caution of such linear thinking may, on the surface, seem reasonable, but in reality, it is simply wrong.

Exhibit 4: Automotive lithium-ion battery demand, IEA forecast vs. actuals, GWh/y

5. The drivers of change will strengthen

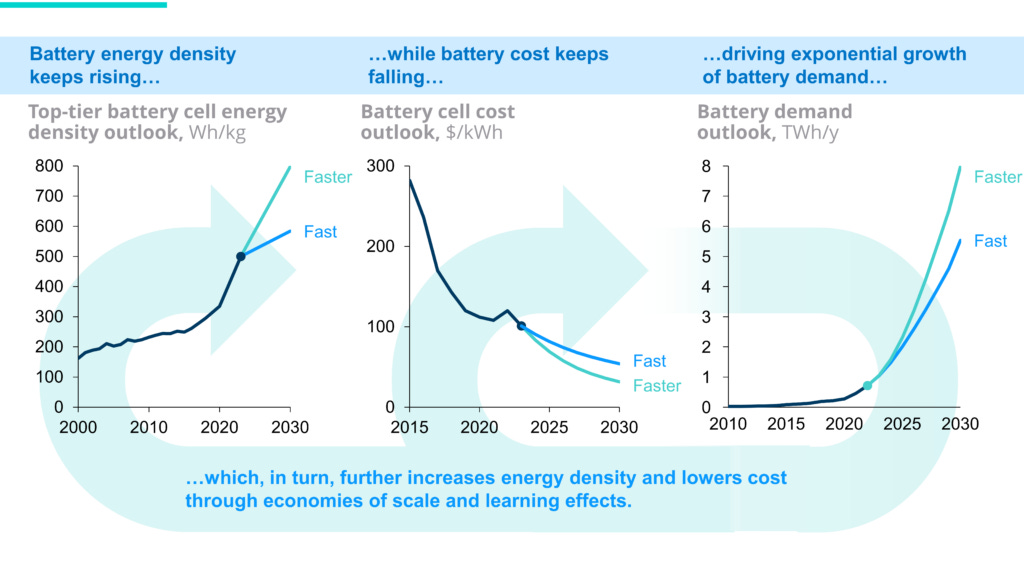

If we look forward to the next seven years, we see the drivers of change strengthening. Notably, we see costs continuing to fall, policy support continuing to rise, and competition between economic blocs continuing to drive a race to the top. And while there are barriers to battery adoption on the horizon, humanity’s wit, will, and capital are scaling proportionally faster. Thus, we do not see a scenario of slow adoption as credible; instead, we model two futures: fast or faster. Reality is likely to lie somewhere between the two.

RMI forecasts that in 2030, top-tier density will be between 600 and 800 Wh/kg, costs will fall to $32–$54 per kWh, and battery sales will rise to between 5.5–8 TWh per year. To get a sense of this speed of change, the lower-bound (or the “fast” scenario) is running in line with BNEF’s Net Zero scenario. The faster S-curve scenario exceeds it.

Exhibit 5: A reinforcing feedback loop between battery quality, cost and market size

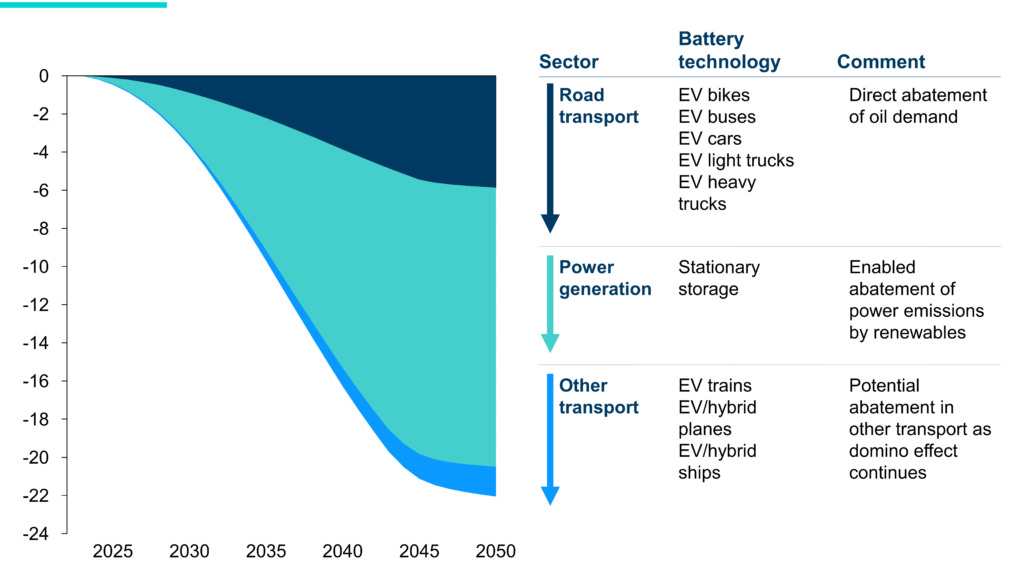

6. Enabling the phase-out of fossil fuels

The best strategy to rapidly phase out fossil fuels is to accelerate the deployment of technologies that reduce fossil fuel demand. Batteries are on the path to displace 86 exajoules (EJ) of fossil fuels from road transport (emitting 6 GtCO2 per year) and to put at risk another 23 EJ (or 1.6 GtCO2/y) from shipping and aviation. In the electricity sector, as batteries synchronize the natural rhythms of the sun and the wind with the timing of electricity demand, they help enable the reduction of a further 175 EJ of fossil fuel demand (or almost 15 GtCO2/y).

Exhibit 6: CO2 emissions abatement enabled by batteries, GtCO2/y abatement versus emissions today

Batteries are growing fast, but that’s no reason to rest on our laurels. Continued growth will require continued effort. Batteries got this far through tireless, concerted efforts of companies, governments, researchers, and climate advocates. And whether the motivation is lower prices, geopolitical advantage, or climate, it is essential to make this fast transition faster.

Flying battery powered planes, and cargo ships. For sure. Unlimited resource availability and zero environmental impact. Zero recycling or end of life analysis. Zero fossil fuel used for manufacturing them. What a techno hopium thing i have just read

Battery costs have declined 99% since 1991? I didn't see that the last time I bought a new battery for my car. Or AA batteries. Oh, wait - this must apply only to one specific type of battery, right? Is this only for Lithium Ion batteries? But lithium ion batteries are still more expensive per kWh than lead batteries.

Demand is growing faster than the projections? But why? Could it be caused by political mandates that car makers sell, and drivers buy, electric vehicles? This adoption is boosted by generous subsidies for the few people who buy electric cars, but we can't really subsidize everyone. What happens to demand when the subsidies stop? Will voters be willing to pay more to buy electric vehicles, more to maintain them, with shorter life than conventional cars? Or will the political settlement fall apart?

Does the Rocky Mountain Institute do any serious analysis, or are they just the booster club for the hoped-for zero carbon revolution?