On 16th November the ETC released a seminal report on the role of fossil fuels in the energy transition. A few observations on this below.

General

A fresh story. This is much more than a report on fossil fuels. It sets out a fresh perspective on the future energy system. One where fossil fuel demand has already reached a peak and we can spend the next three decades driving it down.

We can do this thing. It is possible and likely that we can achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement. The two primary scenarios get us to 1.5 and 1.7 degrees and are both more aggressive than the IEA’s APS (accelerated policy scenario). It is really helpful to have two scenarios which expect change to be fast or faster.

Detailed solutions. The report summarizes the likely ways to reduce fossil fuel demand for each sector in some detail. From cars to heating to industry to electricity. This is the trademark expertise of the ETC, but brought to a new level.

A wide range of drivers. Whilst other reports focus on policy, this report looks at a much wider range of drivers, including exponential growth, cost falls, and the interaction between policy, technology and innovation. As such it is a better reflection of the messy reality we face.

Radical conclusions. The report sets out some radical conclusions for what this means for policymakers, finance, COP, and fossil fuel companies. Which can be summarized as – do not sanction any new fossil fuel extraction, and get on with building the new world.

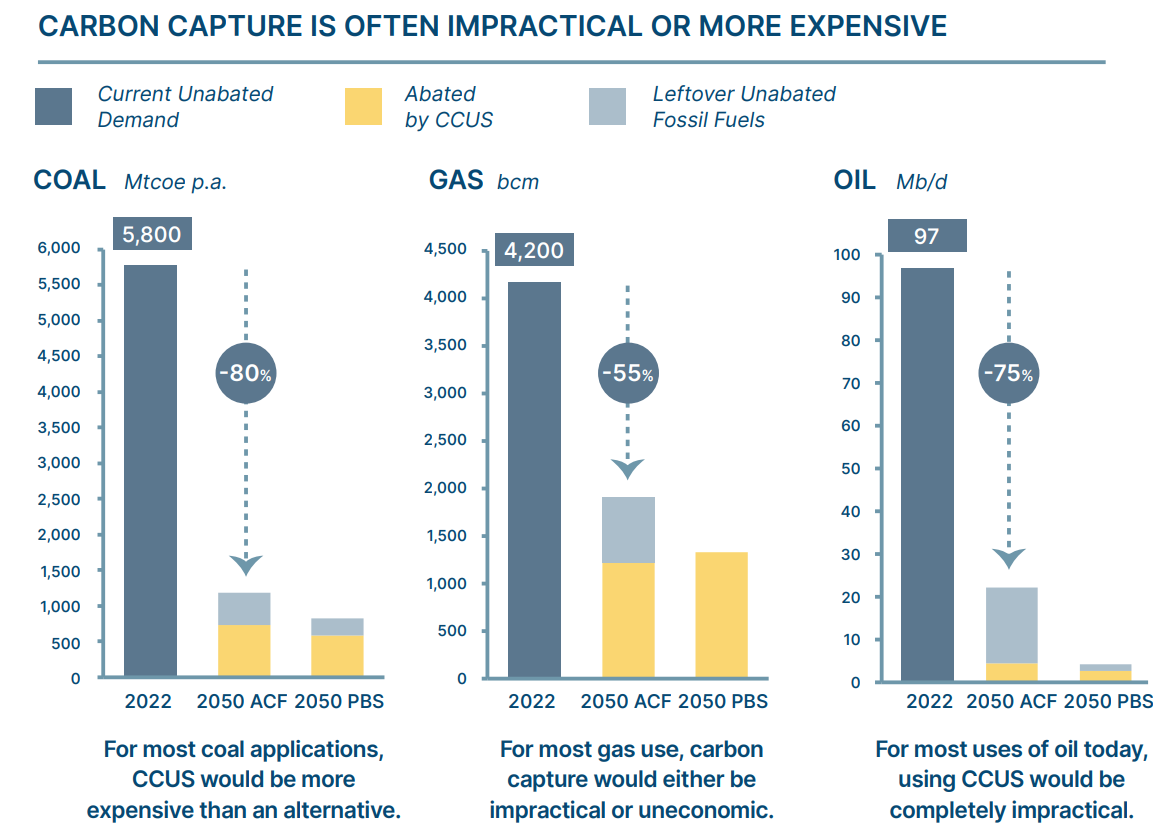

CCS is the last resort. The report is clear that the first thing to do is curtail fossil fuel demand. CCS is only necessary for the last piece of fossil fuel demand that we do not (today) know how to curtail. The report specifically notes the difference between this perspective and that of OPEC, which is to maintain the status quo and try to take the carbon back out of the air.

The fossil fuel sector is planning for far too much growth. The fossil fuel sector (as many others have noted) is planning for supply to continue to grow. There is a huge gap between that and the expected rapid decline under the ETC framing. And that means stranded assets.

What should policymakers do. There are a series of useful suggestions about what policymakers need to do to drive change. They include carbon pricing, fossil bans, and green support. As well as detail – for example, distribution of electricity to EV cars is very feasible, but distribution to trucks requires more action to expand grids.

The report headlines

There are two main scenarios: ACF (Accelerated but clearly feasible) and PBS (Possible but stretching). They are both descriptive in the short term but normative in the long term. It is reasonable to see them as what we can do, not what we will do or what we must do.

What can be done. By 2050, coal use can and must fall around 80-85% from 2022 levels, gas by 55-70%, and oil by 75-95%. We have solutions to reduce fossil fuel demand in 2050 by between 72% and 85% from today’s levels.

We can do a lot by 2030. By 2030, it is possible to cut coal use down around 15-30% by 2030, gas by 15-20% and oil by 5-15%. So fossil fuel demand can fall by between 12% and 20%.

We don't need any new stuff. The world does not need any exploration for new oil and gas fields: any strategy which assumes that all fossil fuel reserves must be exploited is incompatible with limiting global warming to safe levels.

Fossil capex will fall, by 30-35% by 2030 and 45-65% by 2040. Some very limited development of oil and gas is needed to meet short-term demand but much less than companies and countries are currently planning for.

CCS needs to be incremental. It cannot be used to justify business-as-usual fossil fuel production.

Mythbusting

There are answers. There are feasible solutions for a range of areas where people are skeptical. To briefly summarize without doing too much disservice to the detail, they look in depth at solutions (in brackets) to reduce fossil fuel demand in:

Transport: road transport (EV), aviation (hydrogen and SAF), shipping (ammonia and methanol).

Industry: steel (CCS and hydrogen), cement (CCS and alt fuels), petchem (methanol), ammonia (hydrogen) and aluminum (electricity).

Buildings: heating (heat pumps) and cooking (electricity).

Electricity (solar and wind).

There is a lot of low-hanging fruit out there. Fossil fuel demand for road transport and buildings can fall to nearly zero by using EV and heat pumps. In electricity, solar and wind are growing fast. In ammonia you can use green hydrogen and in aluminum you can use green electricity.

The ceiling of the possible keeps rising. As a general point, it is important to note that our ability to solve each of these sectors improves almost every year. The report observes many times that we have many more solutions than we did just two years ago. By implication, in five more years we will have many more answers than those we have today.

Critique on CCS

The report has attracted some controversy because it still has a relatively large role for (highly controversial) CCS, at 7-8 Gt in 2050. Which is more than the IEA, which has 6 Gt of CCS in their latest NZE.

It is best to see CCS as the residual in a 2023 spreadsheet that is trying to solve the entire problem with today’s knowledge levels.

As our technology solutions get better, we will see the need for CCS constantly falling. For example, the power sector in 2050 still has room for 42-51 EJ of fossil fuels, nearly half the residual total. As flexibility technologies improve and renewables get cheaper, that number is highly likely to fall.

The more esoteric CCS solutions, like BECCS, will quietly drop out of the solution suite, in the same way as people have largely given up on the idea of coal plants with CCS at the back.

The key chart.

Find out more here.

Excellent.